An EOSHD opinion.

Humour and creative risk taking are being pulled under by a faceless crowd of sanctimonious trolls. A culture is taking over, heavily pre-disposed to a savage online shaming game. As filmmakers and creative artists we should be aware of what is happening and try to prevent it… because we could be next.

This weekend I read that a senior BBC management figure went so far to compare Clarkson to the sex offender Jimmy Saville, telling a Sunday newspaper in the UK that the star had ‘personal issues’.

As his world-reknowned employer the BBC should be defending the truth and calming the discord – but actually they seem almost as complicit in the shame game as we are.

This is a sea change in how the creative industries operate and reveals a disturbing phenomena that has the potential to affect all filmmakers.

There are millions of people out there, including at the BBC and in the press, who cannot tell the difference between Clarkson’s TV persona and the real person. The problem is most of what people think Clarkson ‘the icon’ represents politically are actually based on his jokes.

Here’s a typical selection of Clarkson jokes – on The French (“Why can’t they just get a life?”) and on animals (“I like pandas. I’d like to own a coat made out of one.”) on liberals (“They don’t wash and they smell of onions”) on green party activists (“I would laugh if they were hit by a runaway industrial waste tanker tomorrow”).

I well understand this brand of humour because Northerners in the UK use it all the time. It’s “taking the piss” and we do it to absolutely everything or anyone. Underneath is an element of banter, sarcasm, warmth. Often it implies a level of affection towards the butt of the joke.

Unfortunately there’s no end of humourless people online who will line up to shame you in public over something you said, explicit or implied, no matter what the context or whether they get the humour.

Now the mainstream press are increasingly feeding off Twitter, the problem is getting worse. Clarkson is just the latest example of someone whose jokes have triggered a dangerous shame game with the potential to ruin his life and career.

Because of what he says on TV, Clarkson is now publicly shamed as a bigoted right wing climate change denier. All because of his fictional TV persona and a string of jokes about cyclists. Even if Clarkson does have that kind of politics, he’s entitled to them as we all are our different political views.

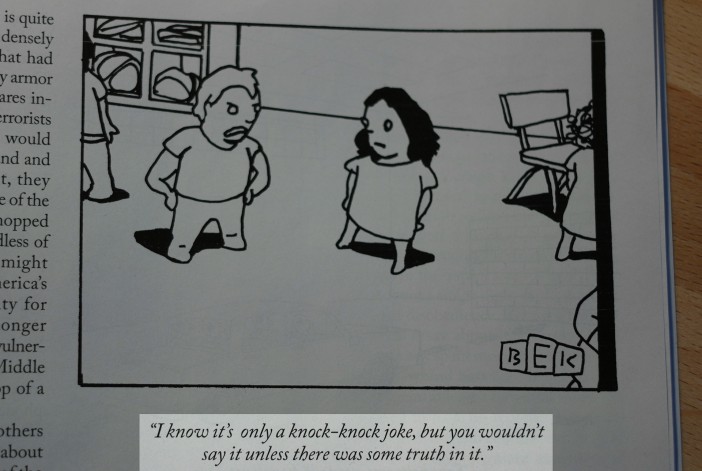

More and more we are defined by what we say on online platforms and like TV, the internet is a broadcast channel. It’s a phenomena is best summed up by Craig Brown’s review of So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed, a book by Jon Ronson (author of The Psychopath Test). The review begins…

“Not long ago I wrote a whimsical little article about being 57. The next day, I made the mistake of looking at the online comments from readers. The first said, simply: ‘I hope you die soon’.

“I looked again, thinking that maybe I had overlooked a subtle bit of irony. But no: someone out there really wanted me dead.

“Jon Ronson’s new book is about the headless monster that lurks within the internet, a monster that bathes in self-righteousness and spouts poison

“It seems to me that the speed and anonymity of the internet has released a demon in otherwise perfectly normal people, transforming them in seconds into spiteful, vengeful, mean-spirited psychopaths.

“Every now and then, their collective self righteousness leaps from out of the hermetic world of the internet and into real life. And when this happens, their randomly selected victim can have his or her reputation destroyed.

“The victims of these public [moral]shamings are many and varied. One of them was a successful 30-year-old PR called Justine Sacco. At the end of 2013, waiting for a flight from Heathrow, she off-handedly tweeted her 170 followers with what was meant to be a joke: “Going to Africa. Hope I don’t get AIDS. Just kidding, I’m white!”

“She intended it as a joke about the sense of entitlement (and immunity) among white people but, like many jokes, it came out all wrong.

“When she arrived at her destination, 11 hours later, she turned her phone back on, to be greeted by a text from someone she hadn’t seen since high school. It read: ‘I’m so sorry to see what’s happened’.

“She wondered what on earth it meant. ‘And then’ she later recalled ‘my phone started to explode’. Unbeknown to her, her silly tweet had, over the course of her flight, become the number one worldwide trend on Twitter.

“One of her followers had retweeted it to a journalist who had re-re-tweeted it to his 15,000 followers. And so on. Within an hour or two, the snowflakes had bundled together to form an avalanche of abuse. In the months before it happened, Sacco had been googled just 30 times; in the 11 days after her ill-judged tweet, she was googled 1,220,000 times.

“Amongst the 100,000 or so who tweeted back, there seemed to be a competition to emerge as the most outraged, the most unforgiving, the most aggressive. ‘No words for that horribly disgusting, racist as fuck tweet from Justine Sacco. I am beyond horrified!’ was pretty typical. Even her employers had tweeted: ‘This is an outrageous, offensive comment. Employee in question currently unreachable.’

“Sacco was forced to cut short her holiday. People were threatening to go on strike at the hotels I was booked into if I showed up,’ she told Ronson. ‘I was told no one could guarantee my safety’.

“On top of all this, she was sacked from her job. ‘Over the years I’ve sat across the tables from a lot of people whose lives had been destroyed’, writes Ronson. ‘… Justine Sacco felt like the first person I had ever interviewed who had been destroyed by us.’

You could say the internet has a created an acid spit snail!

There’s also a political dimension to the Clarkson / BBC row.

A few years ago the BBC’s flagship Newsnight programme made a mysterious editorial decision to drop coverage of a serious scandal involving a powerful politician.

This was seen as a coverup, jeopardising the BBC’s political impartiality and moral journalistic duty.

Most seriously, the BBC were accused of turning a blind eye to Jimmy Saville as well and not just by pulling investigative journalism, but for failing to investigate during decades of serial criminality.

The very same man at the BBC who investigated the very serious allegations over Newsnight, Ken McQuarrie, the director of BBC Scotland, is now beginning his Top Gear inquiry.

The real purpose of this inquiry is that the BBC, politically, now have to be seen to punish misdemeanours by top talents, regardless of context or severity.

This blame culture and public shaming culture is something I as a filmmaker want zero part in, as the same mentality spreads to every corner of the creative industries.

The precedent has been set and over the next week or possibly months (and at great expense), the crew of Top Gear will be investigated formally by an internal BBC team presumably in darkened rooms somewhere at a big London HQ with the potential for their reputations to be shattered in the public shaming match that follows.

The facts of the matter will come out and it could well be established that Clarkson and his producer had a verbal fracas rather than a physical fight.

It won’t matter.

Even after the fact, Clarkson will presumably be sacked anyway because that’s what the BBC promised to do should he cause any further controversy in the easily offended forum of public opinion, a decision made in one fell swoop of a bow to the critics and the press.

The “slope” vietnam-war era banter was the start of the end for Top Gear, and contrary to public opinion – the avoidance of the N-word in a children’s nursery rhyme not the utterance of it added petrol to the fire. Just as public opinion on Justine Sacco destroyed her career over an flippant joke, so it will do for Clarkson and Top Gear.

And my final word on the subject is that the BBC management’s behaviour shows that in the modern broadcast world so much transparency and accountability to the public or customer is involved that it’s nearly impossible for disputes to be solved in private.

Two quarrelling creative talents can no longer simply go to the pub after calming down and overcome their differences like normal people do. Creative talents are now like children, accountable to the real-life ethical demands of their audience and the zero tolerance of their nannying employers.

Those who stand up and defend Clarkson’s narrow remit as an entertainer and not as a messiah out to save the planet from global warming must bear in mind that people will confuse and conflate that defence with defending the politically charged opinions people like to pin to his TV persona, such as casual racism. In the last EOSHD forum thread about the Top Gear controversy some of my own users played the shame game with me, claiming I was endorsing racism and physical violence on set. Perhaps proving all my points made here.

If this is not the perverted culture we want in our creative industries, now is the time to stand up for what we really believe in – the freedom of speech, the importance of humour and tolerance.