With the wholesale shift to mirrorless cameras (Pentax?) the camera world probably thinks it has finally modernised and cosigned the old flappy mirror technology to history (although my Canon 1D C would like a word).

But now there is a new threat to the high end camera market and this time not from itself.

Sensors in smartphones are getting larger. Much larger.

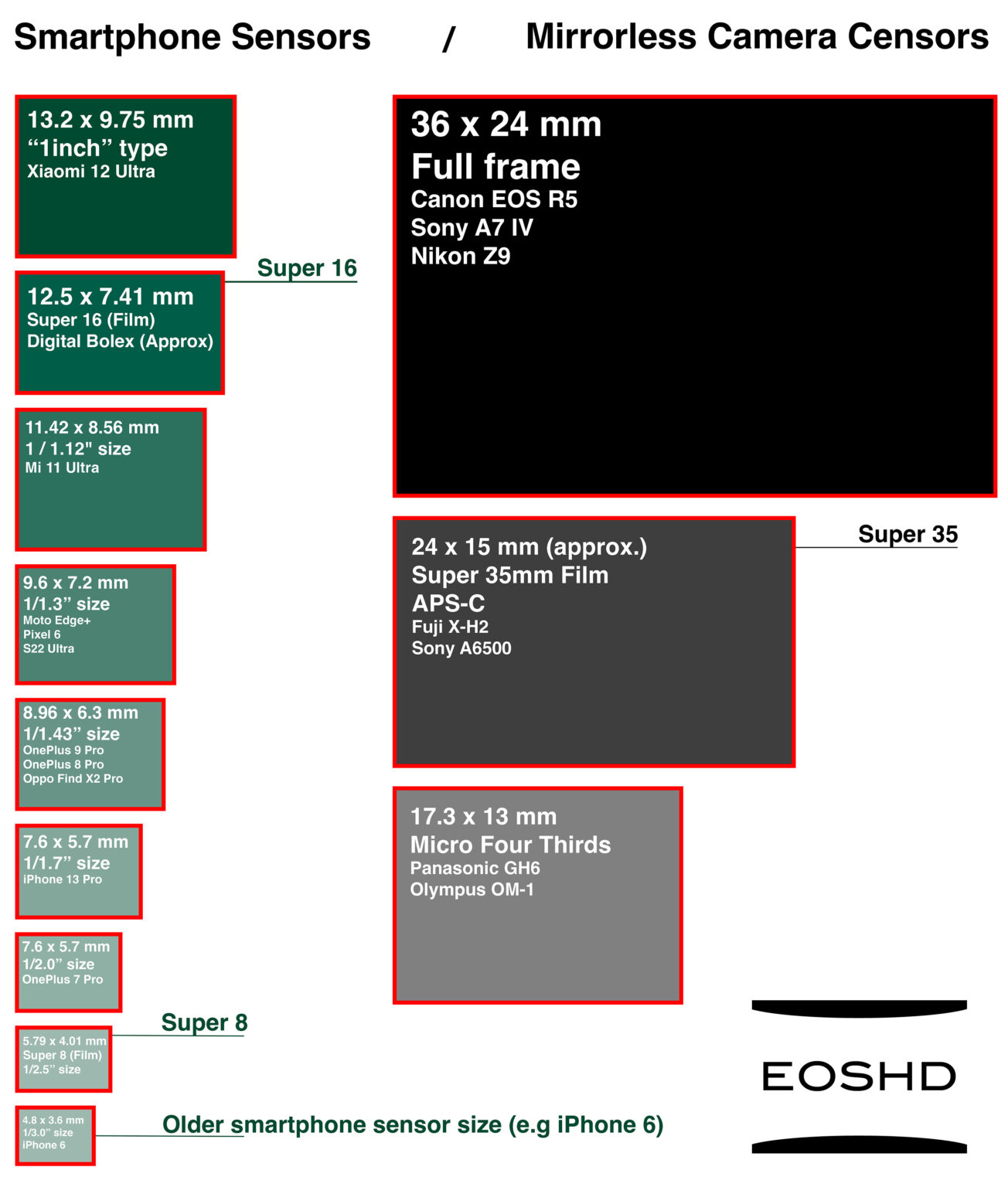

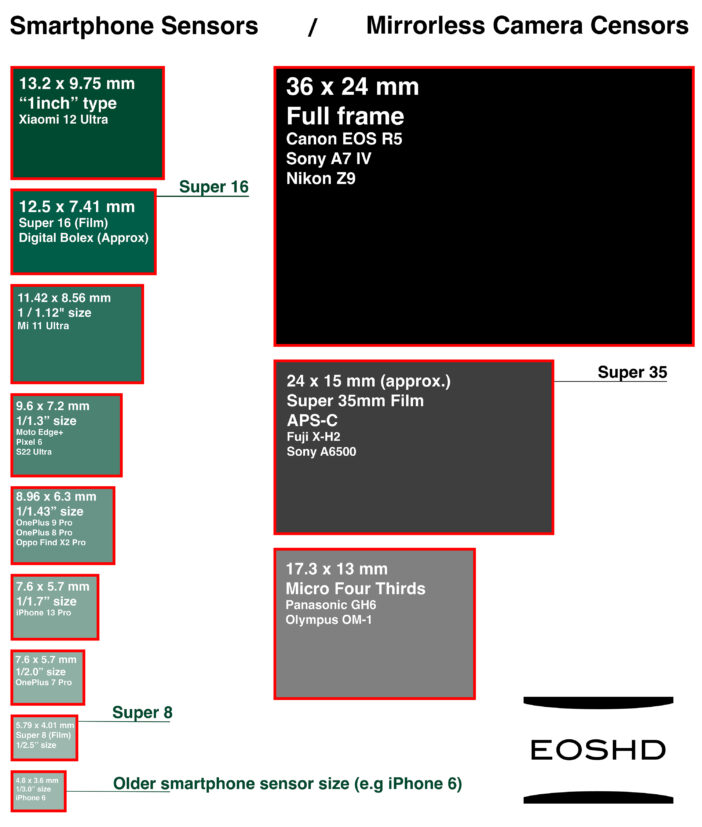

The progress in the last 7 years is remarkable (as my chart above shows). Smartphones have caught up and surpassed Super 16mm. Is Super 35mm next?

Since the iPhone 6 we have gone from main camera modules that were smaller than Super 8 to sensor that are now just 4mm off the width of your Panasonic GH6.

Meanwhile as the enthusiast level of smartphone cameras gets better, there’s a growing demand from journalists and broadcasters for high-end smartphone cameras for their work. For smartphone makers this is the gateway into a new market once dominated by ENG cameras. At this level of use, smartphone cameras challenge the whole concept of a dedicated professional camera body and lens collection.

They’re nimble, discrete, uncomplicated to use. Journalists can be trained to use only what they need to get the job done. A professional cameraman’s role takes years of experience and training. So the appeal is as clear to broadcasters on the economic front as it is to journalists on the creative and content side. The modern journalist is as much a cameraman as a journalist. They are expert multitaskers and becoming proficient dabblers in cinematography.

This is trouble for the Japanese camera makers. It threatens their market not just for cameras but for the highly profitable lenses that go with them. We’re not talking about consumer point & shoot cameras or cheap kit lenses which have already been desecrated by smartphones, but soon the high end and professional stuff is going to be challenged as well.

A lot of this reminds me of how DSLR video began. The improvement of the technology is driven by consumers who want the latest and greatest gizmo. Professionals and filmmakers then come along for the ride and say “we can use this” and the manufacturers s*** themselves and think their market is about to vanish. In 2005 Sony released a very special advancement for the time, a camera with Zeiss 24-120mm F2.8 lens and huge 4K resolution APS-C CMOS sensor. All for less than $1000. Realising that the Sony R1 would annihilate the sales of their DSLRs and lenses if it were to be continually evolved and improved upon, there was to be no Mark II and no subsequent cameras even remotely similar were ever made. Sony must be looking on in absolute angst at smartphones turning into professional broadcast and filmmaking tools. They can’t sell lenses for smartphones, they can’t even seem to grow the sales of their own phones, the market just doesn’t belong to them. All they can do is watch as sister company Sony Semiconductors provide ever better sensors to Xiaomi, Samsung and Apple.

What’s more, Samsung and Sony are putting many times more R&D money into smartphone sensors than into sensors which belong in dedicated standalone cameras which provide for a veritable niche in comparison.

Without meaningfully increasing camera thickness by more than a few millimetres Samsung and Xiaomi have gone 4 leaps forward in sensor size in 3 years. Compared to the current largest sensor in an iPhone (1/1.7″) which measures 7.6mm in width, Android flagships have gone from 1/1.7″ to 1/1.43″ to 1/1.3″ to 1/1.12″ to 1″ type measuring 13.2mm. In just 36 months. That is an almost quadrupling in size of the chip behind the main lens in this time. If this kind of rapid development continues they will reach Super 35mm size in a little over 2 years.

Or will they?

Keeping smartphones pocketable is the key and this means it isn’t as simple as just putting ever larger sensors in phones. The lenses are the important bit, and likely in order to shrink the optics we will need curved sensors or some huge breakthrough to put a 24mm fast prime in a Super 35mm phone measuring no more than 12mm in depth at the thickest part.

Could the industry find a way to make micro lenses work without a traditional optic at all? Could they stitch together a wide field of view from several telephoto lenses with 1″ sensors behind them? It seems to me they are always one major breakthrough away from huge advancements in imaging. Even without a breakthrough in optics, I think they will get to Micro Four Thirds size sensors in smartphones by 2025 regardless.

The space required for the sensor is less of an issue as the battery is taking up a medium format size space in the phone already, so by increasing the power efficiency of the processor and reducing the size of the battery you get plenty of room to work a Super 35mm sensor into a flagship sized device.

The more important question for me is whether smartphones even need to go ever greater sized imaging areas. Evolution didn’t bother with full frame for our retinas, and the results are exceptional thanks to computational imaging and a neural network. A sensor can progress in so many other ways – faster, more dynamic range, more powerful processing behind it. You can even argue that computational imaging benefits from a smaller sensor due to such a deep depth of field. A larger sensor ‘bakes in’ focus distance at the time of the shot.

Then there’s the price factor to consider. Take the Poco X4 Pro for example which has a 1/1.53″ sensor, larger than the iPhone 13 Pro Max. It is 12K in terms of total resolution, 108 megapixel. It costs $300. There is no way the camera industry can compete with that kind of economy of scale.

The response from the camera industry is clear for me. They must get e-sim and 5G network capabilities in cameras and take apps seriously from now on.

Interesting times ahead.