Did you hear of the man who tried to clean every last spec of dust from his Hasselblad?

He’s dead now.

But he has a cautionary tale from beyond the grave…

He liked photography so much, he sold his family to a North Korean slave farm. He never regretted spending the money on a Hasselblad, but one night he decided to take it to pieces… there was a spec of dust in the viewfinder. “Was it really worth it?” he began to wonder, to sell his dear wife and children into slavery for a slow and dusty camera the size of a brick?

Absolutely, thought the man, as he polished the sensor in his Hasselblad digital back for the 10,000th time.

He’s still there now, but his heart no longer beats, his airless lungs no longer breathe and his skeleton has a very unergonomic posture at the desk. His Mac is still working though, loading Sigma Photo Pro.

Like that fateful skeleton, I’ve planned for a while to start doing photos properly, and not with the small crop sensor of a full frame camera.

What’s the closest we can get to a competitive digital 645 format in 2017 for under $3000?

See the word “cheap” in my clickbait PetaPixel inspired headline? Cheap compared to what? A toaster? Not quite.

Nevertheless, like a crocodile waiting patiently in a lake popular with tourists, I’ve been waiting for the right moment to spring onshore to snap up the small child of a wealthy portrait photographer. After scoring a bargain Hasselblad H3D-39II kindly pointed out on my very own forum, I then scoured eBay for the choice of 2 lenses I could afford, before settling on one lens after seeing the price of the second. Let’s just say it’s a good job I enjoy the 80mm focal length on medium format, which is roughly equivalent to 56mm on my full frame camera, with it’s silly small crop sensor.

Here’s what I learnt about choosing an affordable digital body along the way…

Depth and perspective

If you have ever taken a photo of the moon or a solar eclipse with an iPhone, you’ll notice that both the sun and moon have been moved further away by god. (He hates smartphones).

On a smartphone, the moon looks like a street light, a pin prick of light in the sky.

What would it be like to be the favoured one under the Lord Jesus, and be a Hasselblad medium format shooter?

For these privileged people, god brings the sun and moon closer to your camera so you can appreciate superior image quality. Here, an 80mm lens brings objects in the background closer, that’s depth compression, and the large sensor maintains a wider field of view than a small sensor with such a long focal length, so you can pack nice things in around the moon. With a Hasselblad get to have your moon and eat it.

The timeline of digital medium format

When you visit the Hasselblad website today you see a picture of a drone. Hasselblad are now owned by the Chinese company DJI.

The reasons for the Chinese buying Hasselblad is presumably unrelated to taking pictures of the moon (or on it), instead their focus is on the Earth – medium format cameras and very large sensors are used quite a lot in aerial photography… And in spy satellites.

I know professional cat photographer Philip Bloom loves his Pentax 645Z, but Hasselblad is where it’s at. Whereas the Hasselblad H3D-39II with it’s Kodak KAF39000 sensor measures 49 x 36mm, the 50 megapixel Sony CMOS in the Pentax 645Z, Fuji GFX and Hasselblad X1D is a puny 44 x 33mm.

That’s a 1.3x crop over the proper 645 film format.

These new digital medium format cameras are affordable by the standards of the industry but still entry-level hardware, for $7000+ and for that you still don’t quite see the edges of your lenses.

Looking back, the image quality coming of age of digital medium format happened around 2006…

- 1991 – First digital back by Leaf released with 4MP CCD, tethered to a studio computer. Square sensor is approximately 30 x 30 mm similar in size to a full frame SLR (2x crop vs true medium format)

- 1994 – First scanning back by Leaf reaches 6MP in full frame 35mm format but still nowhere near medium format 645 size. Compatible with Phase One and Hasselblad MF film bodies

- 1999 – Resolution hits 10MP but cameras still need to be tethered to a computer via SCSI to record images and sensor sizes remain heavily cropped vs true medium format

- 2002 – Hasselblad introduce modern H system* at Photokina with autofocus and compatibility with a variety of digital backs. All optics made by Fujinon, a big shift for Hasselblad and their long-time association with Zeiss

- 2003 – Kodak 16MP CCD digital backs commonly offered for range of medium format cameras including Hasselblad H1. For the first time they use Compact Flash memory to record internally.

- 2005 – Leaf Aptus digital backs feature touch screen LCDs and 22MP DALSA sensors

- 2006 – Kodak develop breakthrough 39 megapixel CCD (KAF-39000) sensor for medium format digital backs

- 2007 – Fully digital Hasselblad H3D-39 medium format camera released with 39 megapixel Kodak 49 x 36 mm CCD sensor

- 2008 – Dalsa CCD sensors hit 60MP mark with Phase One P65+ as Kodak released 50 megapixel updated to 2006 flagship 39MP sensor

- 2010 – Hasselblad and Pentax (645D) introducing entry-level 40MP Kodak CCD based models with 1 stop improvement in noise but tighter 1.3x crop vs 645 format

- 2012 – CCD manufacturing and development peaks and reaches end-of-life. Switch to CMOS imminent for medium format market

- 2014 – 50MP medium format CMOS sensor (1.3x crop) from Sony features in Pentax 645Z. Advantages include live-view and high ISOs

* Hasselblad’s H system bodies exist until the present day with the 100 megapixel H6D that shoots raw 4K video. From 2007’s “H3D” onwards, the cameras would be designed particularly for digital with better integration, at the expense of compatibility with digital backs from other companies. Digital back manufacturer Leaf are now a subsidiary of Phase One, who bought Japanese medium format camera company Mamiya.

The largest and most rapid leaps in my opinion appear between 2004 and 2007. In 2006 Kodak developed a 1.1x crop 645 39MP sensor without microlenses which was their flagship high resolution chip. This monstered the 20-something megapixel CCDs of the previous few years. They also released a 1.3x crop 31MP CCD with microlenses – these tiny lenses above each pixel were to focus light into each photon receptor resulting in better low light performance. Microlenses are a technology still in use today on all modern sensors. By the turn of the century Kodak and Dalsa were on the verge of making huge strides in CCD technology while CMOS sensors were still in their infancy. In 2005 a high-end CMOS sensor was only APS-C format and in terms of resolution hadn’t yet broken the 10 megapixel mark.

What to buy on eBay?

We need to find a sweet spot at around $3000 with superb resolution that stands up today vs the Sony A7R II, at least at ISO 100.

Because right now for $3000 you can shoot in the region of 42MP on a mirrorless camera or DSLR…

Thankfully such matters have depressed prices on the used market for CCD medium format digital backs and camera bodies.

In 2007 the H3D39-II cost close to $39,000 for just the ready to shoot camera and digital back – now it is closer to $3000 on eBay!

This behemoth camera consists of the modular Hasselblad H system camera, viewfinder and lens mount, which integrates with the Hasselblad 39-II digital back, that actually has an OLED screen. I was rather taken aback by that considering OLED displays were rarely found 10 years ago.

The sweet spot is in the middle of the timeline circa 2006-07, with the Leaf Aptus equipped Phase One P45+ and Hasselblad H3D-39II giving the best bang for buck in terms of image quality at around the $3500 mark on eBay for camera body + back. These both have the legendary 49 x 36 mm 39MP Kodak KAF-39000 sensor.

The Pentax 645D from 2010 can also be considered for around $2500, it’s 1-stop cleaner so ISO 400 looks like 200 on the Hasselblad and it has a much higher resolution LCD screen, 920k vs 230k on the Hasselblad – that said the LCD isn’t a priority for me and neither is the ability to get away with ISO 400 instead of 200! I’d prefer to take the Hasselblad optics, viewfinder, ergonomics, wonderful modular design and larger sensor to the Pentax’s DSLR style body with smaller 1.3x crop sensor and inferior optics. As the viewfinder is removable on the Hasselblad you can clean the dust from it and even swap it completely for a vertical loupe viewfinder, the Hasselblad HVM for around $250.

There are two versions of the Hasselblad H3D-39 – the mark I and mark II. The H3D-39II is the one to try and get hold of as it does away with the noisy fan and has a larger screen – 3″ OLED (yes… OLED!) compared to the older models 2.2″. The battery life is very good on the 39II as well. Old LCD panels, old processors and fans sucked a lot of juice.

The Mamiya 645 AFD and Phase One 645DF are also available on eBay, found frequently between £450 and £750 for the camera body – but it’s getting hold of the digital backs that’s harder. I find the older Leaf backs very rare. The newer Phase One digital backs are still extremely expensive. The $1500-if-you-can-find-it Leaf Aptus 22 don’t really come up to the benchmark set by the Hasselblad H39-II either in terms of image quality, or integration on the camera side. I also find the Phase One bodies ergonomically inferior to the Hasselblad system.

If you can find a Dalsa sensor equipped Leaf Aptus 22 back for under $1000 though, that would be considered a bargain and it does great colour. The Leaf backs aren’t just made to fit Phase One cameras. There’s one for a Hasselblad H body, but this is even rarer than the others! There is even a Hasselblad V version for the vintage cameras and lovely Zeiss lenses… Expect to pay more for that one, if you ever find it.

Above: There’s few F2.0 or faster medium format glass (image courtesy of MemoiresPhotographiques)

One reason to go for the Mamiya 645 AFD bodies are the cheaper lenses and the rather special 80mm F1.9 – one of the fastest aperture lenses ever made for medium format which gives a Leica Noctilux style shallow DOF. It’s only $350. The autofocus Hasselblad 100mm F2.2 HC for the H3D is much more expensive, tending to fetch a minimum of $1800. It’s a lot sharper though.

The manual focus lenses for Mamiya are cheaper still – you can get a 55mm F2.8 for around $150, whereas the same autofocus lens for a Hasselblad would be $900 and that’s if you’re lucky.

What I love about the Hasselblad is that the battery doubles as a grip, and powers the back not just the camera. The Mamiya 645 AFD has batteries in the camera and a separate battery on the Leaf digital back. Here’s the Leaf Aptus 22 back for a Mamiya / Phase One camera…

This takes a $10 Samsung battery on the base, and has a stylus driven touchscreen for settings like ISO, etc. The screen is 2005 vintage and there’s a fan whirring away inside.

It’s not the refined experience of the Hasselblad cameras!

The Hasselblad H3D-39 II communicates very well with the camera with the major stuff controlled on the camera body, not just on the back screen.

Until 2002 it was common for medium format digital backs to be tethered to a computer in the studio recording images to a large hard drive… but as processing advanced by 2003 medium format cameras were able to shoot 20MP images internally to Compact Flash and larger IBM Microdrives around 40GB in size. This was very special for the time, and 20 megapixel resolution cameras with 32GB cards are still considered competitive today… but for $300 not $60,000.

Unless you want to tether your camera via SCSI to a Powermac G4, make sure the digital back has a Compact Flash card slot!

The huge advances between 2006 and 2010 mean the better digital backs are still in demand with pros so you won’t be getting a 60-80MP back which still leads in resolution today. These are selling for upwards of $15,000!

Sensor size

Medium format sensors tend to come in 1.3x, 1.1x and 1.0x crops over 645 format. 44 x 34mm for entry level cameras, mid-to-high end is 49 x 36mm and the very high-end like Phase One P65+ is 53 x 40mm.

The Hasselblad H3D-39 of 2007 is nice and big at 49 x 36mm, but not quite as large as the $40,000 Phase One and Hasselblad flagships of today with their 53 x 40mm sensors (the legendary Sony 100MP CMOS in the Hasselblad H6D-100 that shoots 4K video is one such sensor).

Compare all that to a full frame DSLR sensor… We consider it big at 34 x 24mm! Super 35mm and APS-C are just 23 x 15mm!

Colour and resolution

CCDs have in my view always had quite a filmic response straight off the card in the raw files.

CMOS has a cleaner but almost plastic texture and colour. Almost most CMOS sensors are 14bit, whereas the Kodak 39MP sensor in the Hasselblad H3D-39II is 16bit.

As for resolution, it wasn’t until Sony’s breakthrough in 2012 with the 36MP full frame sensor in the Nikon D800 and the 50MP medium format sensor of 2014 that CMOS got anywhere near close to a high-end 60MP CCD for medium format. Today, it is only with Sony’s very exclusive 100MP CMOS that it truly beats the older CCD sensors for resolution.

100MP is approximately 11K, although total resolution would be less than 100MP on a wide-aspect ratio 11K cinema camera. Meanwhile 50MP is approximately 8K horizontal. 39MP is 7K and in the H3D-39 is without an anti-aliasing filter so I consider that plenty of resolution – here’s an example of what you get from the raw files…

1:1 crop of the 39MP raw file –

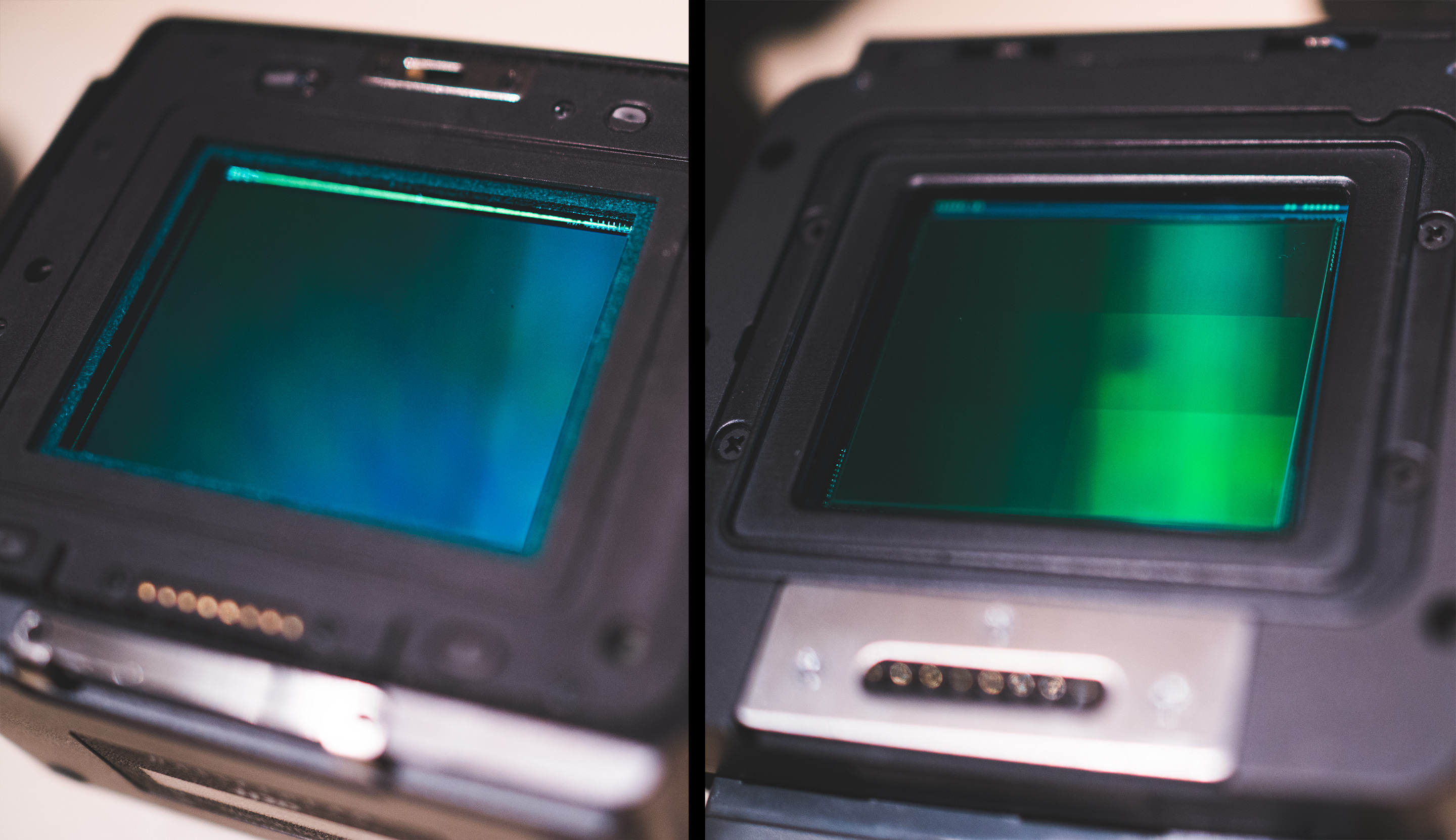

With the older digital backs, to mass-produce such large sensors at the turn of the century, they had to slice them up. You might notice some of them look like 6 sensors stitched together…

If one of the sensors came off the production line a dud, they only had to scrap a smaller proportion of the wafer and not a ginormous expensive chunk of it.

Here’s the 6 blocks evident on the Aptus Leaf 22 (Dalsa sensor, right), but oddly not evident on the Hasselblad’s Kodak chip (left):

Noise

Although these cameras have enormous sensors, CCDs have always had an inherent weakness at high ISOs vs CMOS. Even the best modern CCD medium format cameras of 2012 were really ISO 100 cameras.

On the Hasselblad H3D-39II, ISO 50 is base ISO instead of 200 on a modern camera. This can help outdoor shoots actually, as the Hasselblad cameras use leaf shutters instead of the usual DSLR focal plane shutter. The older Hasselblad H lenses have a maximum leaf shutter speed of 1/800 so being able to drop the sensor to ISO 50 in bright light will lessen the need for ND filters.

At ISO 200 the sensor has some pattern noise in the shadows when pushed dramatically in post, no big deal. ISO 400 is a step down in quality though, and ISO 800 is a dramatic step down – really considered the maximum. That said, even the best Kodak and Dalsa CCDs never pushed meaningfully past ISO 1600 to this day.

These cameras eat light for breakfast, lunch and dinner. Although the CCDs of 2012 are a bit cleaner by about 2 stops to the 2007 vintage sensors, that’s not much and is down to the addition of microlenses, less read noise and other tweaks – there isn’t a big difference in noise at ISO 100 where you’d use it most.

Dynamic range

Throughout the boom in CCD and CMOS technology between 2000 and 2010 dynamic range has stayed at a steady 12 stops on so many cameras…

Dynamic range isn’t a very big differentiating factor when it comes to choosing an older used medium format camera, it only becomes a factor if you compare the new Sony medium format CMOS sensors to the old CCDs – there you definitely have less noise and more detail in the shadows when pushed (on cameras like the Pentax 645Z).

However dynamic range is not all about dynamic range, it’s about how colour performs across the range of luminance in the scene, and this is where 16bit CCDs do a really natural job vs CMOS, in my opinion.

Drawbacks

The Hasselblad H3D-39II isn’t as large as I expected, but it is hefty. Heavier than a 1D X for sure. The Hasselblad 80mm F2.8 HC is nice and small but some of the other lenses in particular the 50-110mm zoom are HUGE and 2kg+! Then there’s the lens prices which have remained lofty, but not as lofty as the original $4000+ price tags!

The OLED screen has a low resolution and very bad visibility outdoors. It’s one of the oldest OLED panels in existence and for 2006 you can’t expect it to match a modern smartphone screen! If you treat the H3D as a film camera with an enormous viewfinder, no live view and a screen you use mainly for the menus you won’t be too disappointed! Zooming in on a shot preview to check focus is pointless – it takes forever to un-pixilate the image when zoomed in and when it does, it’s still not particularly sharp looking.

The Hasselblad H3D-39II can tether to your Mac via firewire 800 (with the Thunderbolt adapter dongle – it would’t be Apple with out a dongle!) and you get a very slow monochrome live-view image but also instant high quality download of the full 39MP images into the retouching software – great for studio portrait work.

Thankfully the H3D body does have quite fast phase-detect AF, although ultimately the speed and reliability lags quite far behind that of a modern DSLR.

You don’t really need live-view for manual focus thanks to the amazing viewfinder. Even at F2.8 you can manually focus very accurately through it.

Conclusion

Beyond just resolution and sharpness, there’s a reason medium format is so favoured by fashion photographers, studio and portrait artists… A small sensor has an impact on perspective and the geometry of faces, especially for close-ups. Small sensors need wider lenses. Smartphone lenses are around 4mm. The wide lens pushes objects in the distance further back. To see what I mean do a portrait with a wide angle 24mm lens on full frame at close proximity – it distorts the face, moving the ears back from the eyes, elongating the nose and narrowing the head. It’s not very flattering!

Perspective as the human eye sees it is far more medium format-like. We compress depth whilst maintaining wide peripheral version.

On medium format a 50mm is approximately 28mm in full frame terms, quite wide but more flattering of faces.

In terms of a shallow depth of field, F2.8 on medium format looks like F1.4 on a full frame camera and F4 looks like F2, but with far higher optical performance across the frame. It is an amazing look and unique to medium format.

In fact a good 80mm F2.8 lens might be the only one you ever need on a Hasselblad.

Just as well, that is the only one I can afford!